Machine Learning Methods For Material Sciences

Machine Learning Fundamentals

Overview

Questions

What are the fundamental concepts in ML I can use in sklearn framewrok ?

How do I write documentation for my ML code?

How do I train and test ML models for material Sciences Problems?

Objectives

Gain an understanding of fundamental machine learning concepts relevant to material sciences.

Develop proficiency in optimizing data preprocessing techniques for machine learning tasks in Python.

Learn and apply best practices for training, evaluating, and interpreting machine learning models in the domain of material sciences.

Apply similarity metrics (e.g., cosine similarity) to quantify structural resemblance

Materials Properties Datasets

These datasets compute properties of various materials.

dc.molnet.load_bandgap : V2 dc.molnet.load_perovskite : V2 dc.molnet.load_mp_formation_energy : V2 dc.molnet.load_mp_metallicity : V2 [3] Lopez, Steven A., et al. “The Harvard organic photovoltaic dataset.” Scientific data 3.1 (2016): 1-7.

[4] Ramsundar, Bharath, et al. “Is multitask deep learning practical for pharma?.” Journal of chemical information and modeling 57.8 (2017): 2068-2076.

What is a Fingerprint?

Deep learning models almost always take arrays of numbers as their inputs. If we want to process molecules with them, we somehow need to represent each molecule as one or more arrays of numbers.

Many (but not all) types of models require their inputs to have a fixed size. This can be a challenge for molecules, since different molecules have different numbers of atoms. If we want to use these types of models, we somehow need to represent variable sized molecules with fixed sized arrays.

Fingerprints are designed to address these problems. A fingerprint is a fixed length array, where different elements indicate the presence of different features in the molecule. If two molecules have similar fingerprints, that indicates they contain many of the same features, and therefore will likely have similar chemistry.

DScribe

DScribe is a Python package for transforming atomic structures into fixed-size numerical fingerprints. These fingerprints are often called “descriptors” and they can be used in various tasks, including machine learning, visualization, similarity analysis, etc. The libary introduce the descriptor and demonstrate their basic call signature. We have also included several examples that should cover many of the use cases.

- Coulomb Matrix

- Sine matrix

- Ewald sum matrix

- Atom-centered Symmetry Functions

- Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions

- Many-body Tensor Representation

- Local Many-body Tensor Representation

- Valle-Oganov descriptor

DScribe provides methods to transform atomic structures into fixed-size numeric vectors. These vectors are built in a way that they efficiently summarize the contents of the input structure. Such a transformation is very useful for various purposes, e.g.

- Input for supervised machine learning models, e.g. regression.

- Input for unsupervised machine learning models, e.g. clustering.

- Visualizing and analyzing a local chemical environment.

- Measuring similarity of structures or local structural sites. etc.

# https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2019.106949

#!pip install dscribe

import numpy as np

from ase.build import molecule

from dscribe.descriptors import SOAP, CoulombMatrix

# ========================================

# 1. Define Atomic Structures

# ========================================

print("Building molecular samples...")

samples = [

molecule("H2O"), # Water (3 atoms)

molecule("NO2"), # Nitrogen dioxide (3 atoms)

molecule("CO2") # Carbon dioxide (3 atoms)

]

# Print basic info

for i, mol in enumerate(samples):

formula = mol.get_chemical_formula()

atomic_numbers = mol.get_atomic_numbers()

print(f"Sample {i}: {formula}, atoms = {len(mol)}, atomic numbers = {atomic_numbers}")

# ========================================

# 2. Setup Descriptors

# ========================================

print("\nSetting up descriptors...")

# Coulomb Matrix: Global molecular descriptor

cm_desc = CoulombMatrix(

n_atoms_max=3,

permutation="sorted_l2" # Ensures consistent ordering

)

# SOAP: Local environment descriptor

soap_desc = SOAP(

species=["H", "C", "N", "O"], # All elements in the dataset

r_cut=5.0, # Cutoff radius in Å

n_max=8, # Number of radial basis functions

l_max=6 # Number of angular basis functions

)

# ========================================

# 3. Coulomb Matrix for Single and Multiple Systems

# ========================================

print("\n--- Computing Coulomb Matrices ---")

# Single molecule (H2O)

water = samples[0]

cm_single = cm_desc.create(water)

print(f"Coulomb Matrix (H2O) shape: {cm_single.shape}")

print(f"Coulomb Matrix (flattened): {cm_single}")

# Batch: All molecules

cm_batch = cm_desc.create(samples)

cm_batch_parallel = cm_desc.create(samples, n_jobs=2)

print(f"Batch Coulomb matrices shape: {cm_batch.shape}") # (3, 9)

print(f"Parallel batch shape: {cm_batch_parallel.shape}")

# ========================================

# 4. SOAP Descriptors for Oxygen Atoms Only

# ========================================

print("\n--- Computing SOAP Descriptors for Oxygen Atoms ---")

# Find oxygen atom indices in each molecule

oxygen_indices = [np.where(mol.get_atomic_numbers() == 8)[0] for mol in samples]

print(f"Oxygen atom indices per molecule: {oxygen_indices}")

# Compute SOAP only for oxygen atoms

oxygen_soap_list = soap_desc.create(samples, oxygen_indices, n_jobs=2)

# Output is a list of arrays (variable number of centers per molecule)

print(f"SOAP output type: {type(oxygen_soap_list)}")

for i, soap_per_mol in enumerate(oxygen_soap_list):

mol_formula = samples[i].get_chemical_formula()

print(f" Molecule {i} ({mol_formula}): {soap_per_mol.shape} SOAP vectors")

# Flatten into a single 2D array: (N_total_oxygens, n_features)

oxygen_soap_flat = np.vstack(oxygen_soap_list)

print(f"Flattened SOAP descriptors shape (all oxygen atoms): {oxygen_soap_flat.shape}")

# Example: (5, 3696) → 1 (H2O) + 2 (NO2) + 2 (CO2)

# ========================================

# 5. Compute SOAP Derivatives (w.r.t. Atomic Positions)

# ========================================

print("\n--- Computing SOAP Derivatives ---")

try:

derivatives_list, descriptors_list = soap_desc.derivatives(

samples,

centers=oxygen_indices,

return_descriptor=True,

n_jobs=1 # Derivatives often work best with n_jobs=1

)

# 'derivatives_list' is a list: one entry per molecule, shape (n_centers, 3, n_features)

print("SOAP derivatives computed successfully (returned as list).")

print(f"Number of molecules in derivatives: {len(derivatives_list)}")

for i, d in enumerate(derivatives_list):

print(f" Molecule {i}: derivative shape = {d.shape}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error computing derivatives: {e}")

# ========================================

# 6. Final Summary

# ========================================

print("\n--- Summary ---")

print(f"Total molecules: {len(samples)}")

print(f"Coulomb Matrices: shape {cm_batch.shape} → used for global molecular representation")

print(f"SOAP (oxygen atoms): flattened to {oxygen_soap_flat.shape} → ready for machine learning")

if 'derivatives_list' in locals():

total_deriv_centers = sum(d.shape[0] for d in derivatives_list)

print(f"SOAP derivatives: {total_deriv_centers} centers total → useful for force prediction")

else:

print("SOAP derivatives: not available")

The above example employs atomistic descriptors to generate machine-readable representations of small inorganic molecules—H₂O, NO₂, and CO₂—using the DScribe library. Two distinct types of descriptors are utilized: the Coulomb Matrix (CM) and the Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP). The CM provides a global, rotation- and permutation-invariant representation of each molecule, encoded as a fixed-size vector of dimension $ n_{\text{atoms}}^{\text{max}} \times n_{\text{atoms}}^{\text{max}} $, here flattened to a 9-dimensional vector after sorting by L2 norm to ensure consistency across configurations. This representation is suitable for regression tasks targeting global molecular properties such as total energy.

In contrast, the SOAP descriptor offers a local, chemically rich description of atomic environments, computed specifically for oxygen atoms across all structures. Due to the variable number of oxygen atoms per molecule (one in H₂O, two in NO₂ and CO₂), the resulting descriptors are structured as a list of arrays, later concatenated into a unified feature matrix of shape (5, 3696), where each row corresponds to an oxygen-centered environment and columns represent the high-dimensional SOAP basis expansion ($ n_{\text{max}} = 8 $, $ l_{\text{max}} = 6 $). This localized approach enables atom-centered machine learning models, including those predicting partial charges, chemical shifts, or reactivity.

Furthermore, analytical derivatives of the SOAP descriptor with respect to atomic positions are computed, enabling the prediction of forces in energy-conserving machine learning potentials. These derivatives are returned per center and per Cartesian direction, forming a hierarchical structure suitable for integration into gradient-based learning frameworks.

The use of parallelization via the n_jobs parameter demonstrates scalability for larger datasets. Overall, this work establishes a reproducible pipeline for generating physically meaningful descriptors from molecular geometries, forming a foundation for subsequent applications in quantum property prediction, potential energy surface construction, and interpretative analysis in computational chemistry and materials informatics.

Coulomb Matrix (CM)

Coulomb Matrix (CM) is a simple global descriptor which mimics the electrostatic interaction between nuclei. Coulomb matrix is calculated with the equation below.

\[M_{ij}^\mathrm{Coulomb} = \begin{cases} 0.5 Z_i^{2.4} & \text{for } i = j \\ \frac{Z_i Z_j}{R_{ij}} & \text{for } i \neq j \end{cases}\]In the matrix above the first row corresponds to carbon (C) in methanol interacting with all the other atoms (columns 2-5) and itself (column 1). Likewise, the first column displays the same numbers, since the matrix is symmetric. Furthermore, the second row (column) corresponds to oxygen and the remaining rows (columns) correspond to hydrogen (H). Can you determine which one is which?

Since the Coulomb Matrix was published in 2012 more sophisticated descriptors have been developed. However, CM still does a reasonably good job when comparing molecules with each other. Apart from that, it can be understood intuitively and is a good introduction to descriptors.

from dscribe.descriptors import CoulombMatrix

from ase.build import molecule

# Define methanol molecule (example)

methanol = molecule("CH3OH")

# Setting up the CM descriptor with max atoms 6

cm = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6)

# Create CM output for methanol

cm_methanol = cm.create(methanol)

print("Coulomb matrix for methanol:\n", cm_methanol)

# Create output for multiple systems

samples = [molecule("H2O"), molecule("NO2"), molecule("CO2")]

# Serial creation

coulomb_matrices_serial = cm.create(samples)

print("Serial Coulomb matrices shape:", coulomb_matrices_serial.shape)

# Parallel creation using 2 jobs (if supported)

coulomb_matrices_parallel = cm.create(samples, n_jobs=2)

print("Parallel Coulomb matrices shape:", coulomb_matrices_parallel.shape)

# No sorting

cm_none = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6, permutation='none')

cm_methanol_none = cm_none.create(methanol)

print("\nChemical symbols:", methanol.get_chemical_symbols())

print("Coulomb matrix without sorting:\n", cm_methanol_none)

# Sort by Euclidean (L2) norm

cm_sorted = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6, permutation='sorted_l2')

cm_methanol_sorted = cm_sorted.create(methanol)

print("Coulomb matrix sorted by L2 norm:\n", cm_methanol_sorted)

# Random permutation

cm_random = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6, permutation='random', sigma=70, seed=None)

cm_methanol_random = cm_random.create(methanol)

print("Coulomb matrix with random permutation:\n", cm_methanol_random)

# Eigenspectrum

cm_eigen = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6, permutation='eigenspectrum')

cm_methanol_eigen = cm_eigen.create(methanol)

print("Eigenspectrum of Coulomb matrix:\n", cm_methanol_eigen)

Coulomb matrix for methanol:

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Serial Coulomb matrices shape: (3, 36)

Parallel Coulomb matrices shape: (3, 36)

Chemical symbols: ['C', 'O', 'H', 'H', 'H', 'H']

Coulomb matrix without sorting:

[36.8581052 33.73297539 5.50690929 3.08170819 5.47078813 5.47078813

33.73297539 73.51669472 3.96011613 8.24741496 3.808905 3.808905

5.50690929 3.96011613 0.5 0.35443545 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.08170819 8.24741496 0.35443545 0.5 0.42555057 0.42555057

5.47078813 3.808905 0.56354208 0.42555057 0.5 0.56068143

5.47078813 3.808905 0.56354208 0.42555057 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix sorted by L2 norm:

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix with random permutation:

[ 0.5 0.56354208 3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.56354208

0.56354208 0.5 3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56068143

3.96011613 3.808905 73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.808905

5.50690929 5.47078813 33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.47078813

0.35443545 0.42555057 8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.42555057

0.56354208 0.56068143 3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.5 ]

Eigenspectrum of Coulomb matrix:

[ 9.55802663e+01 1.81984422e+01 -8.84554212e-01 -4.08434021e-01

-6.06814298e-02 -5.02389071e-02]

The descriptor is computed both for individual molecules and batches, with support for parallel computation via the n_jobs parameter to improve efficiency on multiple structures.

This approach exemplifies how molecular structure data can be systematically converted into machine-learning-ready descriptors while handling permutation symmetries and computational performance, facilitating tasks such as property prediction and molecular similarity analysis in cheminformatics and materials informatics.

invariance tests (translation, rotation, permutation)

Incorporating the invariance tests (translation, rotation, permutation) of the methanol molecule, as well as showing that the Coulomb Matrix descriptor is not designed for periodic systems (pbc set to True). The following code uses ASE methods to manipulate the molecule and demonstrates that the Coulomb matrix remains invariant or changes accordingly.

from dscribe.descriptors import CoulombMatrix

from ase.build import molecule

import numpy as np

# Build methanol molecule

methanol = molecule("CH3OH")

# Initialize Coulomb Matrix descriptor with permutation sorted by L2 norm (invariance)

cm = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6, permutation="sorted_l2")

# Original Coulomb matrix

cm_methanol = cm.create(methanol)

print("Original Coulomb matrix:")

print(cm_methanol)

# --- Invariance tests ---

# Translation: translate methanol by vector (5, 7, 9)

methanol_translated = methanol.copy()

methanol_translated.translate((5, 7, 9))

cm_methanol_translated = cm.create(methanol_translated)

print("\nCoulomb matrix after translation:")

print(cm_methanol_translated)

# Rotation: rotate methanol 90 degrees about the z-axis around origin

methanol_rotated = methanol.copy()

methanol_rotated.rotate(90, 'z', center=(0, 0, 0))

cm_methanol_rotated = cm.create(methanol_rotated)

print("\nCoulomb matrix after rotation:")

print(cm_methanol_rotated)

# Permutation: reverse atom order (upside down)

upside_down_methanol = methanol.copy()[::-1]

cm_methanol_permuted = cm.create(upside_down_methanol)

print("\nCoulomb matrix after permutation (atom reorder):")

print(cm_methanol_permuted)

# --- Periodic boundary conditions (not supported) ---

# Set periodic boundary conditions (PBC) and unit cell (not for molecules)

methanol_pbc = methanol.copy()

methanol_pbc.set_pbc([True, True, True])

methanol_pbc.set_cell([[10.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 10.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.0, 10.0]])

cm_no_perm = CoulombMatrix(n_atoms_max=6) # Default permutation

cm_methanol_pbc = cm_no_perm.create(methanol_pbc)

print("\nCoulomb matrix with periodic boundary conditions (not recommended):")

print(cm_methanol_pbc)

Original Coulomb matrix:

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix after translation:

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix after rotation:

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix after permutation (atom reorder):

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

Coulomb matrix with periodic boundary conditions (not recommended):

[73.51669472 33.73297539 8.24741496 3.96011613 3.808905 3.808905

33.73297539 36.8581052 3.08170819 5.50690929 5.47078813 5.47078813

8.24741496 3.08170819 0.5 0.35443545 0.42555057 0.42555057

3.96011613 5.50690929 0.35443545 0.5 0.56354208 0.56354208

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.5 0.56068143

3.808905 5.47078813 0.42555057 0.56354208 0.56068143 0.5 ]

The sine matrix captures features of interacting atoms in a periodic system with a very low computational cost. The matrix elements are defined by

\[M_{ij}^\mathrm{sine} = \begin{cases} 0.5\, Z_i^{2.4} & i = j \\ \displaystyle \frac{Z_i Z_j}{\left| \mathbf{B} \cdot \sum_{k=x,y,z} \hat{\mathbf{e}}_k \sin^2\left( \pi \hat{\mathbf{e}}_k \mathbf{B}^{-1} \cdot (\mathbf{R}_i - \mathbf{R}_j) \right) \right|} & i \neq j \end{cases}\]where:

- $Z_i$: atomic number

- $\mathbf{R}_i$: position of atom $ i $

- $\mathbf{B}$: matrix of lattice vectors

It is part of the Crystal Metric Representations (CMR) family and is designed for fast, scalable materials comparison.

Exercise: Generating Sine Matrix Fingerprints

The Sine Matrix (SM) is a simple, computationally efficient fingerprint for crystalline solids that captures long-range atomic interactions in a translationally and rotationally invariant manner. It is particularly useful for high-throughput screening and similarity analysis in materials databases. In this exercise, you will:

- Construct a set of common inorganic crystals using

ASE.- Compute the Sine Matrix descriptor for each material using

DScribe.- Explore the structure of the Sine Matrix: diagonal (self-term) vs. off-diagonal (interaction) elements.

- Visualize the descriptor vectors (flattened matrices) using heatmaps and bar plots.

- Compare fingerprints across different crystal structures (e.g., rocksalt vs. diamond).

This exercise focuses exclusively on fingerprint generation, not on property prediction or model training.

Solution

import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import seaborn as sns from ase.build import bulk from dscribe.descriptors import SineMatrix # ======================================== # 1. Build Inorganic Crystal Structures # ======================================== print("Building crystalline materials...\n") # Note: 'cesium_chloride' not supported; using 'bcc' template cscl = bulk("Cs", "bcc", a=4.12, cubic=True) cscl.set_chemical_symbols(["Cs", "Cl"]) # Cs at (0,0,0), Cl at (0.5,0.5,0.5) materials = [ bulk("Si", "diamond", a=5.43), # Diamond cubic bulk("NaCl", "rocksalt", a=5.64), # Rocksalt cscl, # CsCl structure (fixed) bulk("GaAs", "zincblende", a=5.65), # Zincblende bulk("ZnO", "wurtzite", a=3.25, c=5.21) # Wurtzite ] names = ["Si", "NaCl", "CsCl", "GaAs", "ZnO"] for i, name in enumerate(names): natoms = len(materials[i]) formula = materials[i].get_chemical_formula() print(f"{name}: {formula}, atoms = {natoms}, structure = {materials[i].pbc}") # ======================================== # 2. Setup Sine Matrix Descriptor # ======================================== print("\nSetting up Sine Matrix descriptor...") sm_desc = SineMatrix( n_atoms_max=8, # Maximum number of atoms in unit cell permutation="none" # Keep original atom order ) # Compute Sine Matrix (output is always flattened in DScribe >=0.5) fingerprints = sm_desc.create(materials) print(f"Flattened fingerprint shape: {fingerprints.shape}") # (n_samples, 64) # Reshape to get matrix form: (n_samples, 8, 8) sine_matrices = fingerprints.reshape(len(materials), 8, 8) print(f"Sine Matrix output shape: {sine_matrices.shape}") # (n_samples, 8, 8) # ======================================== # 3. Analyze Sine Matrix Structure # ======================================== for i, name in enumerate(names): M = sine_matrices[i] # (8, 8) n_actual = len(materials[i]) print(f"\n--- {name} Sine Matrix Summary ---") diag_mean = np.diag(M)[:n_actual].mean() off_diag_vals = M[~np.eye(M.shape[0], dtype=bool)] # Off-diagonal elements only off_diag_mean = off_diag_vals.mean() print(f" Diagonal (self-interaction) mean: {diag_mean:.3f}") print(f" Off-diagonal (interaction) mean: {off_diag_mean:.3f}") print(f" Max value: {M.max():.3f}, Min value: {M.min():.3f}") # ======================================== # 4. Visualize Sine Matrices # ======================================== fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize=(12, 8)) axes = axes.flatten() for i, name in enumerate(names): M = sine_matrices[i] sns.heatmap( M, ax=axes[i], cmap="Blues", cbar=True, square=True, cbar_kws={"shrink": 0.8} ) axes[i].set_title(f"{name} Sine Matrix") # Remove last subplot fig.delaxes(axes[-1]) plt.suptitle("Sine Matrix Fingerprints for Crystalline Materials", fontsize=14) plt.tight_layout() plt.savefig("sine_matrix_heatmaps.png", dpi=150) plt.show() # ======================================== # 5. Compare Flattened Fingerprints # ======================================== plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) x_pos = np.arange(fingerprints.shape[1]) # Feature index colors = ["tab:blue", "tab:orange", "tab:green", "tab:red", "tab:purple"] for i, name in enumerate(names): plt.plot(x_pos, fingerprints[i], color=colors[i], label=name, linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.8) plt.xlabel("Feature Index (Flattened Sine Matrix)", fontsize=12) plt.ylabel("Descriptor Value", fontsize=12) plt.title("Comparison of Flattened Sine Matrix Fingerprints", fontsize=13) plt.legend() plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3) plt.tight_layout() plt.savefig("sine_matrix_fingerprints.png", dpi=150) plt.show() # ======================================== # 6. Compute Pairwise Similarity # ======================================== print("\nPairwise Cosine Similarity Between Fingerprints:") from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity sim_matrix = cosine_similarity(fingerprints) np.set_printoptions(precision=3, suppress=True) print("Similarity matrix:") print(sim_matrix) # Heatmap of similarity plt.figure(figsize=(6, 5)) sns.heatmap( sim_matrix, annot=True, xticklabels=names, yticklabels=names, cmap="Reds", vmin=0.5, vmax=1.0 ) plt.title("Cosine Similarity Between Sine Matrix Fingerprints") plt.tight_layout() plt.savefig("sine_matrix_similarity.png", dpi=150) plt.show()

Ewald Sum Matrix for Periodic Crystals

The Ewald Sum Matrix (ESM) extends the concept of the Coulomb matrix to periodic systems by modeling the full electrostatic interaction between atomic cores in a crystal, including long-range Coulomb forces and a neutralizing background. It is particularly useful for capturing charge distribution effects and electrostatic stability in ionic materials.

Exercise: Ewald Sum Matrix

The Ewald Sum Matrix (ESM) extends the Coulomb matrix to periodic systems by modeling the full electrostatic interaction between atomic cores in a crystal, including long-range Coulomb forces and a neutralizing background. It is particularly useful for capturing charge distribution effects and electrostatic stability in ionic materials.

In this exercise, you will:

- Construct common crystals (NaCl, Al, Fe) using

ASE.- Set up the Ewald Sum Matrix descriptor using

DScribe.- Compute ESMs for single and multiple systems (serial and parallel).

- Explore how convergence parameters affect accuracy.

- Estimate the total electrostatic energy of a crystal from the ESM.

This exercise focuses on descriptor generation and physical interpretation, not on machine learning.

Solution

# 1. Import and Setup import numpy as np import scipy.constants import math from ase.build import bulk from dscribe.descriptors import EwaldSumMatrix print("Setting up systems and descriptor...\n") # Create NaCl crystal nacl = bulk("NaCl", "rocksalt", a=5.64) al = bulk("Al", "fcc", a=4.046) fe = bulk("Fe", "bcc", a=2.856) # List of samples for batch processing samples = [nacl, al, fe] names = ["NaCl", "Al", "Fe"] for name, atoms in zip(names, samples): formula = atoms.get_chemical_formula() print(f"{name}: {formula}, atoms = {len(atoms)}, cell = {atoms.cell.lengths()[0]:.3f} Å") # 2. Setup Ewald Sum Matrix Descriptor esm = EwaldSumMatrix( n_atoms_max=6 ) # 3. Create ESM for Single System print("\nCreating ESM for NaCl...") nacl_ewald = esm.create(nacl, flatten=False) print(f"NaCl ESM shape: {nacl_ewald.shape}") # 4. Create ESM for Multiple Systems print("\nCreating ESM for multiple systems (serial)...") ewald_matrices = esm.create(samples, flatten=False) # Serial print(f"Batch ESM shape: {ewald_matrices.shape}") print("\nCreating ESM in parallel (n_jobs=2)...") ewald_matrices_parallel = esm.create(samples, n_jobs=2, flatten=False) # 5. Vary Accuracy via Alpha (Convergence Parameter) print("\nTesting different convergence parameters (alpha)...") ewald_1 = esm.create(nacl, alpha=2.0) # Lower accuracy ewald_2 = esm.create(nacl, alpha=4.0) # Higher accuracy print(f"Low-alpha fingerprint norm: {np.linalg.norm(ewald_1):.2f}") print(f"High-alpha fingerprint norm: {np.linalg.norm(ewald_2):.2f}") # 6. Calculate Total Electrostatic Energy print("\nCalculating total electrostatic energy for Al (example)...") # Use a symmetric system (Al is neutral, Z=3) ems = EwaldSumMatrix( n_atoms_max=2, # FCC Al has 1 atom conventional → expand or use 2-atom cell permutation="none", sigma=1.0, alpha=3.0 ) # Use 2-atom cell to see interactions al_expanded = al * (2, 1, 1) # Now has 2 atoms ems_out_flat = ems.create(al_expanded) ems_out = ems.unflatten(ems_out_flat)[0] # Extract first (only) system # Total electrostatic energy ≈ sum of all entries divided by 2 (each interaction counted twice) # But: ESM includes self-energy and interaction terms total_energy = ems_out.sum() / 2 # Each pair counted twice; self-terms once # Convert from atomic units (e²/Å) to eV conversion = 1e10 * scipy.constants.e / (4 * math.pi * scipy.constants.epsilon_0) total_energy_eV = total_energy * conversion print(f"Total electrostatic energy (approx): {total_energy_eV:.4f} eV") # 7. Summary print("\n💡 Key Points:") print(" • ESM captures long-range electrostatics in periodic systems.") print(" • Use 'alpha' to control real/reciprocal space balance.") print(" • Parallelization via 'n_jobs' speeds up batch processing.") print(" • Total energy can be estimated from sum of ESM entries (with care).")

Machine Learning

The Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) descriptor encodes the local atomic environment by representing the neighboring atomic density around each atom using expansions in spherical harmonics and radial basis functions within a cutoff radius. Parameters such as the cutoff radius, number of radial basis functions, maximum degree of spherical harmonics, and Gaussian smearing width control the descriptor’s resolution and size. The DScribe library efficiently computes these SOAP descriptors along with their derivatives with respect to atomic positions, enabling force predictions.

In machine learning models, the SOAP descriptor \(\mathbf{D}\) serves as the input to predict system properties like total energy through a function \(f(\mathbf{D})\). The predicted forces on atom \(i\), denoted \(\hat{\mathbf{F}}_i\), are obtained as the negative gradient of the predicted energy with respect to that atom’s position \(\mathbf{r}_i\), expressed as:

\[\hat{\mathbf{F}}_i = - \nabla_{\mathbf{r}_i} f(\mathbf{D}) = - \nabla_{\mathbf{D}} f \cdot \nabla_{\mathbf{r}_i} \mathbf{D}\]Here, \(\nabla_{\mathbf{D}} f\) is the derivative of the model output with respect to the descriptor, which neural networks provide analytically, and \(\nabla_{\mathbf{r}_i} \mathbf{D}\) is the Jacobian matrix of descriptor derivatives with respect to atomic coordinates, given by DScribe for SOAP. This equation expands as the dot product between the row vector of partial derivatives of the energy with respect to descriptor components and the matrix of derivatives of each descriptor component with respect to spatial coordinates:

\[\hat{\mathbf{F}}_i = - \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial D_1} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial D_2} & \dots \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial D_1}{\partial x_i} & \frac{\partial D_1}{\partial y_i} & \frac{\partial D_1}{\partial z_i} \\ \frac{\partial D_2}{\partial x_i} & \frac{\partial D_2}{\partial y_i} & \frac{\partial D_2}{\partial z_i} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \end{bmatrix}\]DScribe organizes these derivatives such that the last dimension corresponds to descriptor features, optimizing performance in row-major data formats such as NumPy or C/C++ by making the dot product over the fastest-varying dimension more efficient, although this layout can be adapted as needed.

Training requires a dataset composed of feature vectors \(\mathbf{D}\), their derivatives \(\nabla_{\mathbf{r}} \mathbf{D}\), as well as reference energies \(E\) and forces \(\mathbf{F}\). The loss function is formed by summing the mean squared errors (MSE) of energy and force predictions, each scaled by the inverse variance of the respective quantities in the training data to balance their contribution:

\[\text{Loss} = \frac{1}{\sigma_E^2} \mathrm{MSE}(E, \hat{E}) + \frac{1}{\sigma_F^2} \mathrm{MSE}(\mathbf{F}, \hat{\mathbf{F}})\]This ensures the model learns to predict both energies and forces effectively. Together, these components form a pipeline where SOAP descriptors combined with neural networks and analytic derivatives enable accurate and efficient prediction of atomic energies and forces for molecular and materials simulations.

Dataset preparation

This script prepare a training dataset of Lennard-Jones energies and forces for a simple two-atom system with varying interatomic distances. It uses the SOAP descriptor to characterize atomic environments and includes computation of analytical derivatives needed for force prediction.

import numpy as np

import ase

from ase.calculators.lj import LennardJones

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from dscribe.descriptors import SOAP

# Initialize SOAP descriptor

soap = SOAP(

species=["H"],

periodic=False,

r_cut=5.0,

sigma=0.5,

n_max=3,

l_max=0,

)

# Generate data for 200 samples with distances from 2.5 to 5.0 Å

n_samples = 200

traj = []

n_atoms = 2

energies = np.zeros(n_samples)

forces = np.zeros((n_samples, n_atoms, 3))

distances = np.linspace(2.5, 5.0, n_samples)

for i, d in enumerate(distances):

# Create two hydrogen atoms separated by distance d along x-axis

atoms = ase.Atoms('HH', positions=[[-0.5 * d, 0, 0], [0.5 * d, 0, 0]])

atoms.set_calculator(LennardJones(epsilon=1.0, sigma=2.9))

atoms.cal = cal

traj.append(atoms)

energies[i] = atoms.get_total_energy()

forces[i] = atoms.get_forces()

# Validate energies by plotting against distance

plt.figure(figsize=(8,5))

plt.plot(distances, energies, label="Energy")

plt.xlabel("Distance (Å)")

plt.ylabel("Energy (eV)")

plt.title("Lennard-Jones Energies vs Distance")

plt.grid(True)

plt.savefig("Lennard-Jones_Energies_vs_Distance.png")

plt.show()

# Compute SOAP descriptors and their analytical derivatives with respect to atomic positions

# The center is fixed at the midpoint between the two atoms

derivatives, descriptors = soap.derivatives(

traj,

centers=[[[0, 0, 0]]] * n_samples,

method="analytical"

)

# Save datasets for training

np.save("r.npy", distances)

np.save("E.npy", energies)

np.save("D.npy", descriptors)

np.save("dD_dr.npy", derivatives)

np.save("F.npy", forces)

The energies obtained from the Lennard-Jones two-atom system as a function of interatomic distance typically exhibit a characteristic curve, where the energy decreases sharply as the atoms approach each other, reaches a minimum at the equilibrium bond length, and then rises gradually as the atoms move further apart. This shape reflects the balance between attractive and repulsive forces in the Lennard-Jones potential.

In the plotted energy vs. distance graph, you will see a smooth curve starting at a higher energy around shorter distances (due to strong repulsion), dipping to a minimum energy near the equilibrium separation (around 3.0 Å for the parameters used), and then slowly increasing as the distance increases (weaker attraction).

This energy profile validates the dataset by demonstrating the physically meaningful behavior of the system’s interaction potential, which the machine learning model aims to learn and reproduce.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.svm import SVR

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

# Load dataset (numpy arrays)

D_numpy = np.load("D.npy")[:, 0, :] # SOAP descriptor: one center per sample

E_numpy = np.load("E.npy") # Energies, shape (n_samples,)

F_numpy = np.load("F.npy") # Forces (not used here)

dD_dr_numpy = np.load("dD_dr.npy") # Descriptor derivatives (not used here)

r_numpy = np.load("r.npy") # Distances (optional)

# Select training subset (e.g., 30 points evenly spaced)

n_train = 30

idx = np.linspace(0, len(r_numpy) - 1, n_train).astype(int)

D_train_full = D_numpy[idx]

E_train_full = E_numpy[idx]

# Scale features for better model training

scaler = StandardScaler()

D_train_full_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(D_train_full)

D_numpy_scaled = scaler.transform(D_numpy)

# Optional split train/validation (not mandatory for random forest or SVM)

# Here we use all training points directly for simplicity

# -------------------

# Random Forest Model

# -------------------

rf_model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, random_state=7)

rf_model.fit(D_train_full_scaled, E_train_full)

# Predict energies on full dataset

E_pred_rf = rf_model.predict(D_numpy_scaled)

# Compute mean absolute error on full dataset

mae_rf = mean_absolute_error(E_pred_rf, E_numpy)

print(f"Random Forest Energy Prediction MAE: {mae_rf:.4f} eV")

# -------------------

# Support Vector Machine Model

# -------------------

svm_model = SVR(kernel='rbf', C=10.0, gamma='scale')

svm_model.fit(D_train_full_scaled, E_train_full)

# Predict energies on full dataset

E_pred_svm = svm_model.predict(D_numpy_scaled)

# Compute MAE for SVM

mae_svm = mean_absolute_error(E_pred_svm, E_numpy)

print(f"SVM Energy Prediction MAE: {mae_svm:.4f} eV")

Random Forest Energy Prediction MAE: 0.0830 eV

SVM Energy Prediction MAE: 0.0970 eV

Exercise: Predicting Atomic Forces with Random Forest and SVR

Machine learning models can predict atomic forces — essential for molecular dynamics, geometry optimization, and interatomic potential development. In this exercise, you will:

- Generate a dataset of H₂ dimer configurations using the Lennard-Jones potential.

- Compute SOAP descriptors for each atom in the system.

- Train two models — Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) — using

MultiOutputRegressorto predict 3D atomic forces.- Evaluate performance using Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

- Understand how descriptors and regression strategies enable force learning.

This exercise focuses on force prediction, a core component of machine-learned force fields, and demonstrates the use of multi-output regression for vector-valued targets.

Solution

# 1. Import Libraries and Generate Data import numpy as np import ase from ase.calculators.lj import LennardJones from dscribe.descriptors import SOAP print("Generating H₂ dimer dataset with Lennard-Jones forces...\n") # Initialize SOAP descriptor soap = SOAP( species=["H"], periodic=False, r_cut=5.0, sigma=0.5, n_max=3, l_max=0, ) # Generate 200 samples: H₂ dimer at varying distances n_samples = 200 traj = [] n_atoms = 2 energies = np.zeros(n_samples) forces = np.zeros((n_samples, n_atoms, 3)) # Shape: (200, 2, 3) distances = np.linspace(2.5, 5.0, n_samples) for i, d in enumerate(distances): atoms = ase.Atoms('HH', positions=[[-0.5 * d, 0, 0], [0.5 * d, 0, 0]]) calc = LennardJones(epsilon=1.0, sigma=2.9) atoms.calc = calc traj.append(atoms) energies[i] = atoms.get_total_energy() forces[i] = atoms.get_forces() # Reshape forces for ML: (n_samples * n_atoms, 3) forces_flat = forces.reshape(-1, 3) print(f"Generated {n_samples} configurations with {n_atoms} atoms each.") print(f"Force data shape (flattened): {forces_flat.shape}") # 2. Compute SOAP Descriptors print("\nComputing SOAP descriptors...") centers = [[[0, 0, 0]]] * n_samples # One center per system descriptors = soap.create(traj, centers=centers) # Shape: (200, 1, 6) D = descriptors.squeeze(axis=1) # Remove singleton dim → (200, 6) # Repeat each descriptor for both atoms D_repeated = np.repeat(D, n_atoms, axis=0) # (200, 6) → (400, 6) print(f"SOAP descriptor shape (repeated): {D_repeated.shape}") # 3. Train-Test Split and Scaling from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( D_repeated, forces_flat, test_size=0.2, random_state=7 ) scaler = StandardScaler() X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # 4. Random Forest Model for Force Prediction print("\nTraining Random Forest model on forces...") from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor from sklearn.multioutput import MultiOutputRegressor from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error rf_base = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, random_state=7) rf_model = MultiOutputRegressor(rf_base) rf_model.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) y_pred_rf = rf_model.predict(X_test_scaled) mae_rf = mean_absolute_error(y_test, y_pred_rf) print(f"Random Forest MAE (force): {mae_rf:.4f} eV/Å") # 5. SVR Model for Force Prediction print("\nTraining SVR model on forces...") from sklearn.svm import SVR svr_base = SVR(kernel='rbf', C=10.0, gamma='scale') svr_model = MultiOutputRegressor(svr_base) svr_model.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) y_pred_svr = svr_model.predict(X_test_scaled) mae_svr = mean_absolute_error(y_test, y_pred_svr) print(f"SVR MAE (force): {mae_svr:.4f} eV/Å")

Band Gap

Predicting band gaps using machine learning (ML) is a cutting-edge approach that enables fast and accurate estimation of a material’s electronic band gap—a key property influencing its electronic and optical behavior. ML models leverage extensive material databases and elemental descriptors to predict band gaps efficiently, overcoming the high computational costs and limitations of traditional methods like density functional theory (DFT). By training on known band gap data, ML models such as support vector regression, random forests, and gradient boosting can capture complex relationships between composition and band gap, accelerating the discovery of new materials with desired electronic properties. Additionally, some ML techniques offer interpretable models that provide insight into the physical factors affecting band gaps, making ML a powerful tool in materials science for band gap prediction and material design.

Getting the dataset

In this section, we demonstrate how to retrieve data on stable binary compounds from the Materials Project database using its API. By specifying criteria such as the number of elements and stability (energy above hull), we extract key material properties including chemical formula, symmetry, energy per atom, volume, and magnetization. The retrieved data is organized into a structured pandas DataFrame for easy analysis and further processing. This approach enables efficient access to high-quality materials data for research and machine learning applications.

from mp_api.client import MPRester

import pandas as pd

api_key = 'your_api_key'

fields = [

"material_id", "formula_pretty", "symmetry",

"nsites", "energy_per_atom", "volume",

"energy_above_hull", "total_magnetization"

]

with MPRester(api_key) as mpr:

docs = mpr.materials.summary.search(

num_elements=[2, 2],

energy_above_hull=(0, 0.001),

fields=fields

)

records = []

for doc in docs:

row = {

"material_id": doc.material_id,

"formula": doc.formula_pretty,

"num_sites": doc.nsites,

"energy_per_atom": doc.energy_per_atom,

"volume": doc.volume,

"energy_above_hull": doc.energy_above_hull,

"total_magnetization": doc.total_magnetization

}

if doc.symmetry:

row["spacegroup_number"] = doc.symmetry.number

row["crystal_system"] = doc.symmetry.crystal_system

records.append(row)

df = pd.DataFrame(records)

print("Stable binary compounds count", len(df))

print(df.head())

Retrieving SummaryDoc documents: 100%|█| 5500/5500 [00:03<00:00, 1771.

Stable binary compounds count 5500

material_id formula num_sites energy_per_atom volume \

0 mp-11107 Ac2O3 5 -8.354915 91.511224

1 mp-32800 Ac2S3 40 -34.768478 1118.407852

2 mp-985305 Ac3In 8 -57.372981 309.226331

3 mp-985506 Ac3Tl 8 -64.936750 309.225189

4 mp-866199 AcAg 2 -45.267835 61.529375

energy_above_hull total_magnetization spacegroup_number crystal_system

0 0.0 0.000000e+00 164 Trigonal

1 0.0 0.000000e+00 122 Tetragonal

2 0.0 1.642045e+00 194 Hexagonal

3 0.0 3.199100e-03 194 Hexagonal

4 0.0 6.000000e-07 221 Cubic

The result shows successful retrieval of data for 5,500 stable binary compounds from the Materials Project database. The extracted dataset includes key information such as material ID, chemical formula, number of atomic sites, energy per atom, volume, energy above hull (indicating stability), total magnetization, space group number, and crystal system. The preview of the dataset reveals a diverse set of compounds with a range of structural symmetries and electronic properties, providing a rich resource for further materials analysis and modeling.

Data Augmentation

In this section, we augment experimental band gap datasets by integrating them with structural and energetic data obtained from the Materials Project database. We retrieve stable compounds with 2 to 4 elements and combine these with multiple experimental band gap datasets to create a unified dataset. This merged dataset includes both experimental band gap values and corresponding material properties, facilitating more comprehensive analyses and model training.

from mp_api.client import MPRester

import pandas as pd

from matminer.datasets import load_dataset

api_key = "FAOXV20YqTT2edzIRotOaC2ayHn10cDT"

# query stable compounds with nelements = 2,3,4

fields = [

"material_id", "formula_pretty", "symmetry",

"nsites", "energy_per_atom", "volume",

"energy_above_hull", "total_magnetization"

]

with MPRester(api_key) as mpr:

docs = mpr.materials.summary.search(

num_elements=[2, 4], # range inclusive [2,4]

energy_above_hull=(0, 0.001),

fields=fields

)

records = []

for doc in docs:

row = {

"material_id": doc.material_id,

"formula": doc.formula_pretty,

"num_sites": doc.nsites,

"energy_per_atom": doc.energy_per_atom,

"volume": doc.volume,

"energy_above_hull": doc.energy_above_hull,

"total_magnetization": doc.total_magnetization

}

if doc.symmetry:

row["spacegroup_number"] = doc.symmetry.number

row["crystal_system"] = doc.symmetry.crystal_system

records.append(row)

df1 = pd.DataFrame(records)

print("Stable compounds (2–4 elements)", len(df1))

print(df1.head())

# ---- experimental band gap datasets ----

df2 = load_dataset("matbench_expt_gap")

df2 = df2.rename(columns={"composition": "formula", "gap expt": "gap_expt"})

df2 = df2[["formula", "gap_expt"]]

df3 = load_dataset("expt_gap")

df3 = df3.rename(columns={"formula": "formula", "gap expt": "gap_expt"})

df3 = df3[["formula", "gap_expt"]]

# union of experimental datasets

df4 = pd.concat([df2, df3], ignore_index=True)

df4 = df4[df4["gap_expt"] > 0].drop_duplicates("formula")

print("Experimental band gap entries", len(df4))

print(df4.head())

# ---- merge DFT structural features with experimental gaps ----

df = pd.merge(df1, df4, on="formula", how="inner")

df = df.drop_duplicates("formula", keep="first")

print("Final merged dataset", len(df))

print(df.head())

Retrieving SummaryDoc documents: 100%|██████████| 33972/33972 [00:15<00:00, 2261.30it/s]

Stable compounds (2–4 elements) 33972

material_id formula num_sites energy_per_atom volume \

0 mp-1183076 Ac2AgPb 4 -54.209271 134.563097

1 mp-1183086 Ac2CdHg 4 -52.120621 133.072641

2 mp-862786 Ac2CuGe 4 -40.884684 113.979079

3 mp-861883 Ac2CuIr 4 -50.462576 104.095515

4 mp-867241 Ac2GePd 4 -5.176522 114.834178

energy_above_hull total_magnetization spacegroup_number crystal_system

0 0.0 0.910605 225 Cubic

1 0.0 0.628202 225 Cubic

2 0.0 0.001071 225 Cubic

3 0.0 0.000169 225 Cubic

4 0.0 0.000001 225 Cubic

Experimental band gap entries 3651

formula gap_expt

2 Ag0.5Ge1Pb1.75S4 1.83

3 Ag0.5Ge1Pb1.75Se4 1.51

6 Ag2GeS3 1.98

7 Ag2GeSe3 0.90

8 Ag2HgI4 2.47

Final merged dataset 1050

material_id formula num_sites energy_per_atom volume \

0 mp-9900 Ag2GeS3 12 -4.253843 267.880017

1 mp-1096802 Ag2GeSe3 12 -3.890180 309.160842

2 mp-23485 Ag2HgI4 7 -2.239734 266.737075

3 mp-353 Ag2O 6 -3.860246 107.442223

4 mp-2018369 Ag2S 12 -17.033431 245.557534

energy_above_hull total_magnetization spacegroup_number crystal_system \

0 0.000000 0.0 36 Orthorhombic

1 0.000986 0.0 36 Orthorhombic

2 0.000000 0.0 82 Tetragonal

3 0.000000 0.0 224 Cubic

4 0.000207 0.0 14 Monoclinic

gap_expt

0 1.98

1 0.90

2 2.47

3 1.50

4 1.23

The results show the successful retrieval of 33,972 stable compounds with 2 to 4 elements from the Materials Project database. Additionally, 3,651 experimental band gap entries were obtained from multiple datasets. After merging these datasets based on the formula, a final unified dataset of 1,050 compounds was created. This merged dataset combines theoretical material properties (such as energy per atom, volume, and crystal symmetry) with experimentally measured band gap values, providing a valuable and comprehensive resource for material analysis and predictive modeling. The sample data illustrates a variety of compounds with detailed structural and electronic features alongside their experimental band gaps.

Feature engineering

In this step, we perform feature engineering on the dataset by extracting additional material descriptors from the chemical composition using the pymatgen and matminer libraries. Specifically, we convert the formula strings into Composition objects and apply the AtomicOrbitals featurizer to compute features related to atomic orbital characteristics. These new features enrich the dataset with meaningful chemical information that can improve the accuracy and interpretability of machine learning models for predicting band gaps. Missing values are removed to ensure data quality before further analysis

from pymatgen.core import Composition

from matminer.featurizers.composition import ElementProperty,AtomicOrbitals

df['composition'] = df.formula.map(lambda x: Composition(x))

df = df.dropna(axis=0)

df = AtomicOrbitals().featurize_dataframe(df,

'composition',

ignore_errors=True,

return_errors=False)

(df[df.gap_AO > 0]).head()

df.head()

AtomicOrbitals: 100%|██████████| 1050/1050 [00:12<00:00, 84.01it/s]

material_id formula num_sites energy_per_atom volume energy_above_hull total_magnetization spacegroup_number crystal_system gap_expt composition HOMO_character HOMO_element HOMO_energy LUMO_character LUMO_element LUMO_energy gap_AO

0 mp-9900 Ag2GeS3 12 -4.253843 267.880017 0.000000 0.0 36 Orthorhombic 1.98 (Ag, Ge, S) p S -0.261676 p S -0.261676 0.000000

1 mp-1096802 Ag2GeSe3 12 -3.890180 309.160842 0.000986 0.0 36 Orthorhombic 0.90 (Ag, Ge, Se) p Se -0.245806 p Se -0.245806 0.000000

2 mp-23485 Ag2HgI4 7 -2.239734 266.737075 0.000000 0.0 82 Tetragonal 2.47 (Ag, Hg, I) p I -0.267904 s Hg -0.205137 0.062767

3 mp-353 Ag2O 6 -3.860246 107.442223 0.000000 0.0 224 Cubic 1.50 (Ag, O) d Ag -0.298706 s Ag -0.157407 0.141299

4 mp-2018369 Ag2S 12 -17.033431 245.557534 0.000207 0.0

The results show that the AtomicOrbitals featurizer successfully generated atomic orbital-related features for all 1,050 entries in the dataset. These features include information about the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) characters, elements, and energies, as well as the calculated band gap based on atomic orbital data (gap_AO). The dataset now contains enhanced chemical descriptors such as orbital types (e.g., s, p, d), corresponding elements, and orbital energy levels, which provide deeper insight into the electronic structure of materials and can improve predictive modeling of their band gaps. The feature engineering process completed efficiently with comprehensive coverage across all materials.

Preprocessing features

In this step, we preprocess the atomic orbital character features by converting categorical orbital labels (such as s, p, d, f) into a consistent numeric format. This mapping standardizes the data, making it suitable for machine learning algorithms that require numerical inputs. Unknown or missing values are preserved as NaN to avoid incorrect data transformation, ensuring clean and reliable feature representation for model training.

# define consistent mapping

homo_lomo_mapper = {

"s": 1,

"p": 2,

"d": 3,

"f": 4,

}

# map to numeric, keep NaN for unknowns

df["HOMO_character"] = df["HOMO_character"].astype(str).str.strip().str.lower()

df["LUMO_character"] = df["LUMO_character"].astype(str).str.strip().str.lower()

df["HOMO_character"] = df["HOMO_character"].map(homo_lomo_mapper)

df["LUMO_character"] = df["LUMO_character"].map(homo_lomo_mapper)

df.head()

material_id formula num_sites energy_per_atom volume energy_above_hull total_magnetization spacegroup_number crystal_system gap_expt composition HOMO_character HOMO_element HOMO_energy LUMO_character LUMO_element LUMO_energy gap_AO

0 mp-9900 Ag2GeS3 12 -4.253843 267.880017 0.000000 0.0 36 Orthorhombic 1.98 (Ag, Ge, S) 2 S -0.261676 2 S -0.261676 0.000000

1 mp-1096802 Ag2GeSe3 12 -3.890180 309.160842 0.000986 0.0 36 Orthorhombic 0.90 (Ag, Ge, Se) 2 Se -0.245806 2 Se -0.245806 0.000000

2 mp-23485 Ag2HgI4 7 -2.239734 266.737075 0.000000 0.0 82 Tetragonal 2.47 (Ag, Hg, I) 2 I -0.267904 1 Hg -0.205137 0.062767

3 mp-353 Ag2O 6 -3.860246 107.442223 0.000000 0.0 224 Cubic 1.50 (Ag, O) 3 Ag -0.298706 1 Ag -0.157407 0.141299

4 mp-2018369 Ag2S 12 -17.033431 245.557534 0.000207 0.0 14 Monoclinic 1.23 (Ag, S) 2 S -0.261676 1 Ag -0.157407 0.104269

The results show the dataset after preprocessing, where the HOMO and LUMO orbital characters have been successfully mapped to numerical values (e.g., 1 for s, 2 for p, etc.). The dataset includes detailed material properties such as energy per atom, volume, stability indicators, crystal symmetry, and experimental band gaps alongside these numerical orbital features. This structured and numeric representation of the data is now well-prepared for machine learning applications aimed at predicting material properties based on their atomic and electronic characteristics.

Augment extra featrues

In this step, we augment the dataset with additional descriptive features derived from elemental properties using the Magpie data source. Specifically, we compute the mean atomic weight and covalent radius for each material’s composition. These features, combined with the previously calculated values, such as volume per atom (vpa), provide richer chemical and structural information to improve the performance and interpretability of predictive models.

from matminer.utils.data import MagpieData

desc = ["AtomicWeight", "CovalentRadius"]

stats = ["mean"]

dataset = MagpieData()

ep = ElementProperty(data_source=dataset, features=desc, stats=stats)

df = ep.featurize_dataframe(df,"composition", ignore_errors=True,

return_errors=False)

df['vpa'] = np.array(df['volume']/df['num_sites'])

df.head()

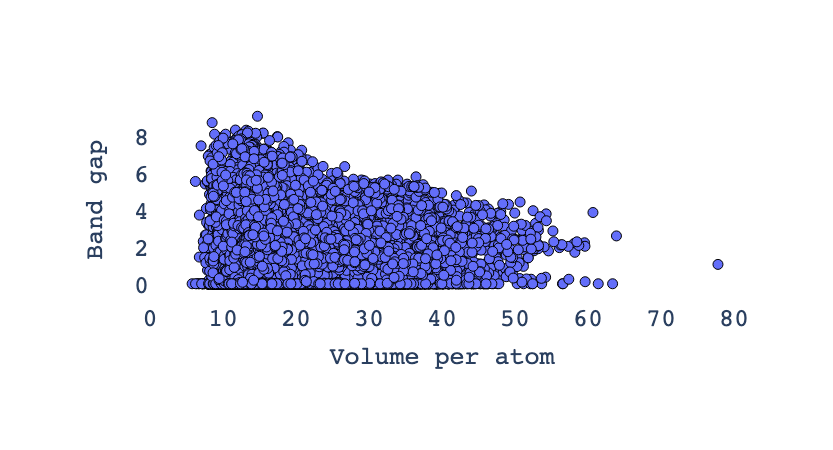

Now let’s utilize the figrecipes library—specifically the PlotlyFig class—to create an interactive scatter plot of volume per atom (vpa) versus band gap for a set of materials. Each point on the plot represents a material, with the color corresponding to its space group number, and the axes showing how the electronic band gap varies as a function of atomic volume. This visualization helps identify trends and relationships between crystal structures and their electronic properties, facilitating material discovery and analysis.

!pip install figrecipes

from figrecipes import PlotlyFig

# plot vpa vs bandgap

pf = PlotlyFig(df, y_title='Band gap', x_title='Volume per atom', filename='bandgap_vpa',mode='notebook')

pf.xy(('vpa', 'band_gap'), labels='spacegroup.number', colorscale='Viridis', limits={'x': (0, 80)})

The inverse relationship in the plot between volume per atom (vpa) and band gap means that as the volume per atom increases, the band gap tends to decrease, and vice versa

Save the preprocessed featrues

In this step, we clean and prepare the dataset for further analysis by dropping rows with missing values and removing irrelevant columns such as material ID, formula, number of sites, and volume. The cleaned and streamlined dataset, containing only the essential features, is then saved to a CSV file named “band_gap_preprocessed.csv” for convenient access and use in subsequent modeling or visualization tasks.

df.dropna(axis=0)

df = df.drop(columns=['material_id', 'formula','num_sites','volume'])

df.to_csv("band_gap_preprocessed.csv",index=0)

Building an ML model

In this section, we build a machine learning model to predict the band gap of materials based on their preprocessed features. We use the Random Forest Regressor, a powerful ensemble learning method, for this regression task. The dataset is split into training and testing subsets to evaluate the model’s performance accurately. After training the model on the training data, we predict band gap values on the test set and assess the prediction accuracy using mean squared error (MSE), which measures the average squared difference between predicted and true values.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

# Initialize the target

y = df.gap_expt.values

y = y.astype(np.float32)

# target variable as 1D float32 array

y = df.gap_expt.values.astype(np.float32)

# features

X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1)

# Split data

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0

)

RF = RandomForestRegressor()

RF.fit(X_train,y_train)

y_pred = RF.predict(X_test_scaled)

mse = mean_squared_error(y_pred, y_test)

mse

Exercise 1: Retrain the Model with Normalized Features Using StandardScaler

Feature scaling is a crucial preprocessing step in machine learning, especially for algorithms sensitive to the magnitude of input features. Although tree-based models like Random Forest are generally robust to feature scales, standardizing the input can still improve numerical stability and help in fair comparison across features. In this exercise, you will:

- Extract the target variable

gap_exptand ensure it is in the correct format.- Prepare the feature matrix by dropping the target column.

- Split the data into training and test sets (80/20).

- Apply

StandardScalerto normalize the features — fitting only on the training set.- Retrain a

RandomForestRegressoron the scaled features.- Evaluate the model using Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the test set.

This exercise emphasizes proper data preprocessing and reinforces best practices in avoiding data leakage during scaling.

Solution

# 1. Use StandardScaler to reduce MSE from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error import numpy as np # Initialize the target y = df.gap_expt.values y = y.astype(np.float32) # Features X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1) # Split data X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0 ) # Initialize scaler scaler = StandardScaler() # Fit scaler on training features and transform training data X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) # Transform test data using the same scaler (do NOT fit again!) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # Train Random Forest model on scaled features RF = RandomForestRegressor(random_state=0) RF.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) # Predict on scaled test set y_pred_scaled = RF.predict(X_test_scaled) # Compute MSE mse_scaled = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_scaled) mse_scaled

Exercise 2: Retrain the Model with Normalized Features Using Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is highly sensitive to the scale of input features, making feature normalization a critical step. Unlike tree-based models such as Random Forest, SVR relies on distance-based computations and can perform poorly if features are not standardized. In this exercise, you will:

- Extract the target variable

gap_exptand ensure it is in the correct format.- Prepare the feature matrix by dropping the target column.

- Split the data into training and test sets (80/20).

- Apply

StandardScalerto normalize both features and the target (optional but often helpful for SVR).- Train a

SVRmodel on the scaled features.- Evaluate the model using Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the test set.

This exercise highlights the importance of feature scaling when working with distance-based models like SVR and contrasts it with less sensitive models such as Random Forest.

Solution

# 1. Use StandardScaler and train an SVR model from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn.svm import SVR from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error import numpy as np # Initialize the target y = df.gap_expt.values y = y.astype(np.float32) # Features X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1) # Split data X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0 ) # Initialize scalers for features and target scaler_X = StandardScaler() scaler_y = StandardScaler() # Scale features X_train_scaled = scaler_X.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler_X.transform(X_test) # Scale target (helps SVR converge faster; inverse transform needed for evaluation) y_train_scaled = scaler_y.fit_transform(y_train.reshape(-1, 1)).ravel() # Train SVR model on scaled features and scaled target svr = SVR(kernel='rbf', C=1.0, epsilon=0.1) svr.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train_scaled) # Predict on scaled test set y_pred_scaled = svr.predict(X_test_scaled) # Inverse transform predictions to original scale y_pred = scaler_y.inverse_transform(y_pred_scaled.reshape(-1, 1)).ravel() # Compute MSE in original scale mse = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred) mse

Exercise 3: Retrain the Model with Normalized Features Using XGBoost

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is a powerful tree-based ensemble method that is inherently robust to feature scaling. However, proper preprocessing—including standardization—can still improve convergence and facilitate fair comparisons across features, especially when integrating with other pipelines or models. In this exercise, you will:

- Extract the target variable

gap_exptand ensure it is in the correct format.- Prepare the feature matrix by dropping the target column.

- Split the data into training and test sets (80/20).

- Apply

StandardScalerto normalize the features — fitting only on the training set.- Train an XGBoost Regressor (

XGBRegressor) on both the original and scaled features (for comparison).- Evaluate both models using Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the test set.

This exercise demonstrates that while XGBoost does not require feature scaling, applying it does not break performance—and helps reinforce best practices in consistent preprocessing workflows.

Solution

# 1. Use StandardScaler and train an XGBoost model from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from xgboost import XGBRegressor from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error import numpy as np # Initialize the target y = df.gap_expt.values y = y.astype(np.float32) # Features X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1) # Split data X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0 ) # Initialize and apply StandardScaler to features scaler = StandardScaler() X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # ======================================== # Option A: Train XGBoost on Original (Unscaled) Features # ======================================== print("Training XGBoost on original features...") xgb_orig = XGBRegressor(random_state=0, n_estimators=100, learning_rate=0.1, max_depth=6) xgb_orig.fit(X_train, y_train) y_pred_orig = xgb_orig.predict(X_test) mse_orig = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_orig) print(f"MSE (Original Features): {mse_orig:.4f}") # ======================================== # Option B: Train XGBoost on Scaled Features # ======================================== print("Training XGBoost on scaled features...") xgb_scaled = XGBRegressor(random_state=0, n_estimators=100, learning_rate=0.1, max_depth=6) xgb_scaled.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) # Note: target not scaled; XGBoost handles it well y_pred_scaled = xgb_scaled.predict(X_test_scaled) mse_scaled = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_scaled) print(f"MSE (Scaled Features): {mse_scaled:.4f}") # ======================================== # Summary # ======================================== print(f"\nComparison:") print(f"Without scaling: MSE = {mse_orig:.4f}") print(f"With scaling: MSE = {mse_scaled:.4f}") print(f"Performance {'improved' if mse_scaled < mse_orig else 'was similar or slightly worse'} with scaling.") # Final return value (scaled version) mse_scaled

Exercise 4 : Compare RandomForest, SVR, and XGBoost Models Using Normalized Features

In this comprehensive exercise, you will retrain and compare three different regression models —

RandomForestRegressor,SVR, andXGBRegressor— using normalized input features. The goal is to evaluate how each model performs on the same dataset after proper preprocessing, highlighting the impact of model choice and sensitivity to feature scaling.You will:

- Extract the target variable

gap_exptand prepare the feature matrix.- Split the data into training and test sets (80/20).

- Apply

StandardScalerto normalize the features (fit only on training data).- Train and evaluate each of the following models:

- RandomForest: Tree-based, robust to scale.

- SVR: Distance-based, highly sensitive to scale.

- XGBoost: Gradient boosting, tree-based, scale-robust but benefits from clean pipelines.

- Use Mean Squared Error (MSE) for comparison.

- Visualize the predictions vs. true values across models.

This exercise emphasizes model comparison, preprocessing best practices, and understanding how algorithmic assumptions affect performance.

Solution

# Compare RandomForest, SVR, and XGBoost with standardized features from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor from sklearn.svm import SVR from xgboost import XGBRegressor from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Initialize the target y = df.gap_expt.values y = y.astype(np.float32) # Features X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1) # Split data X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0 ) # Initialize and apply StandardScaler (only on features) scaler = StandardScaler() X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # Dictionary to store results results = {} # ======================================== # 1. RandomForest Regressor (on scaled features) # ======================================== print("Training RandomForest...") rf = RandomForestRegressor(random_state=0, n_estimators=100) rf.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) y_pred_rf = rf.predict(X_test_scaled) mse_rf = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_rf) results['RandomForest'] = mse_rf print(f"RandomForest MSE: {mse_rf:.4f}") # ======================================== # 2. SVR (Support Vector Regression) - Requires scaling # ======================================== print("Training SVR...") # Scale target for SVR as well scaler_y = StandardScaler() y_train_scaled_svr = scaler_y.fit_transform(y_train.reshape(-1, 1)).ravel() svr = SVR(kernel='rbf', C=1.0, epsilon=0.1) svr.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train_scaled_svr) y_pred_svr_scaled = svr.predict(X_test_scaled) y_pred_svr = scaler_y.inverse_transform(y_pred_svr_scaled.reshape(-1, 1)).ravel() mse_svr = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_svr) results['SVR'] = mse_svr print(f"SVR MSE: {mse_svr:.4f}") # ======================================== # 3. XGBoost Regressor (on scaled features) # ======================================== print("Training XGBoost...") xgb = XGBRegressor(random_state=0, n_estimators=100, learning_rate=0.1, max_depth=6) xgb.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) y_pred_xgb = xgb.predict(X_test_scaled) mse_xgb = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_xgb) results['XGBoost'] = mse_xgb print(f"XGBoost MSE: {mse_xgb:.4f}") # ======================================== # Summary of Results # ======================================== print("\n" + "="*40) print("MODEL COMPARISON (MSE)") print("="*40) for model, mse in results.items(): print(f"{model:>12}: {mse:.4f}") best_model = min(results, key=results.get) print(f"\nBest Model: {best_model} (MSE = {results[best_model]:.4f})") # ======================================== # Visualization: True vs Predicted # ======================================== plt.figure(figsize=(12, 4)) models = ['RandomForest', 'SVR', 'XGBoost'] y_preds = [y_pred_rf, y_pred_svr, y_pred_xgb] mses = [mse_rf, mse_svr, mse_xgb] for i, (name, y_pred, mse) in enumerate(zip(models, y_preds, mses)): plt.subplot(1, 3, i+1) plt.scatter(y_test, y_pred, alpha=0.6, color=['tab:blue', 'tab:orange', 'tab:green'][i]) plt.plot([y_test.min(), y_test.max()], [y_test.min(), y_test.max()], 'r--', lw=2) plt.xlabel("True Values") plt.ylabel("Predictions") plt.title(f"{name}\nMSE = {mse:.4f}") plt.axis('equal') plt.suptitle("True vs Predicted Values for Each Model", fontsize=14) plt.tight_layout() plt.savefig("model_comparison_predictions.png", dpi=150) plt.show() # Final return value: best MSE results[best_model]

# Import necessary libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.svm import SVR

from xgboost import XGBRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, mean_absolute_error, r2_score

# Set style for plots

sns.set(style="whitegrid")

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (10, 6)

# Assume df is already loaded

# y: target variable, X: features

y = df['gap_expt'].values.astype(np.float32)

X = df.drop('gap_expt', axis=1)

# Split the data

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, shuffle=True, random_state=0

)

# Scale the features

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test)

# Define models

models = {

"Random Forest": RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=60, random_state=0),

"XGBoost": XGBRegressor(random_state=0, verbosity=0),

"SVR": SVR()

}

# Dictionary to store results

results = {

"Model": [],

"MSE": [],

"RMSE": [],

"MAE": [],

"R2": []

}

# Store predictions for plotting

predictions = {}

# Train and evaluate each model

for name, model in models.items():

# Fit model

model.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)

# Predict

y_pred = model.predict(X_test_scaled)

predictions[name] = y_pred

# Metrics

mse = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred)

rmse = np.sqrt(mse)

mae = mean_absolute_error(y_test, y_pred)

r2 = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

# Save to results

results["Model"].append(name)

results["MSE"].append(mse)

results["RMSE"].append(rmse)

results["MAE"].append(mae)

results["R2"].append(r2)

print(f"--- {name} ---")

print(f"MSE: {mse:.4f}, RMSE: {rmse:.4f}, MAE: {mae:.4f}, R²: {r2:.4f}\n")

# Convert results to DataFrame for easy viewing

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results)

print("Summary of Model Performance:")

print(results_df)

# === PLOT 1: True vs Predicted Values for Each Model ===

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(18, 5))

axes = axes.flatten()

for i, (name, y_pred) in enumerate(predictions.items()):

ax = axes[i]

ax.scatter(y_test, y_pred, alpha=0.6, color='dodgerblue')

ax.plot([y_test.min(), y_test.max()], [y_test.min(), y_test.max()], 'r--', lw=2)

ax.set_xlabel('True Values (gap_expt)')

ax.set_ylabel('Predicted Values')

ax.set_title(f'{name}: True vs Predicted')

ax.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# === PLOT 2: Comparison of Metrics Across Models (Fixed for Seaborn v0.14+) ===

metrics = ['MSE', 'RMSE', 'MAE', 'R2']

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

axes = axes.flatten()

for i, metric in enumerate(metrics):

ax = axes[i]

# Fixed: Use hue='Model' + legend=False

sns.barplot(data=results_df, x='Model', y=metric, ax=ax, hue='Model', palette="viridis", legend=False)

ax.set_title(f'Comparison of Models - {metric}')

ax.set_ylim(0, max(results_df[metric]) * 1.1)

for j, val in enumerate(results_df[metric]):

ax.text(j, val + max(results_df[metric])*0.01, f'{val:.3f}', ha='center', va='bottom', fontsize=9)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Optional: Display results table

print("\nDetailed Results:")

display(results_df)

adding extra features

# ======================

# IMPORTS

# ======================

from mp_api.client import MPRester

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor, GradientBoostingRegressor

from xgboost import XGBRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, mean_absolute_error, r2_score

from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer # <-- To handle NaNs

from pymatgen.core import Composition

from matminer.featurizers.composition import ElementProperty, OxidationStates, AtomicOrbitals, BandCenter

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

sns.set(style="whitegrid")

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (10, 6)

# ======================

# 1. SET API KEY

# ======================

api_key = "FAOXV20YqTT2edzIRotOaC2ayHn10cDT" # Replace if needed

# ======================

# 2. FETCH DATA

# ======================

print("🔍 Fetching semiconductor materials from Materials Project...")

valid_fields = [

"material_id", "formula_pretty", "nsites", "elements", "density", "volume",

"energy_per_atom", "formation_energy_per_atom", "energy_above_hull", "band_gap",

"is_gap_direct", "total_magnetization", "bulk_modulus", "shear_modulus",

"homogeneous_poisson", "efermi", "universal_anisotropy", "n", "e_total"

]

with MPRester(api_key) as mpr:

docs = mpr.materials.summary.search(

num_elements=[2, 3],

energy_above_hull=(0, 0.1),

is_metal=False,

band_gap=(0.01, None),

chunk_size=100,

num_chunks=10,

fields=valid_fields

)

records = []

for doc in docs:

row = {

"material_id": doc.material_id,

"formula": doc.formula_pretty,

"num_sites": doc.nsites,

"num_elements": doc.nelements,

"density": doc.density,

"volume": doc.volume,

"energy_per_atom": doc.energy_per_atom,

"formation_energy_per_atom": doc.formation_energy_per_atom,

"energy_above_hull": doc.energy_above_hull,

"band_gap": doc.band_gap,

"is_gap_direct": int(doc.is_gap_direct) if doc.is_gap_direct is not None else 0,

"total_magnetization": doc.total_magnetization,

"bulk_modulus": doc.bulk_modulus,

"shear_modulus": doc.shear_modulus,

"poisson_ratio": doc.homogeneous_poisson,

"fermi_energy": doc.efermi,

"elastic_anisotropy": doc.universal_anisotropy,

"refractive_index": doc.n,

"dielectric_constant": doc.e_total,

}

records.append(row)

df_raw = pd.DataFrame(records)

print(f"✅ Retrieved {len(df_raw)} stable semiconductor materials.")

# ======================

# 3. FEATURIZE WITH ERROR HANDLING

# ======================

print("🧪 Engineering composition-based features...")

df_raw['composition'] = df_raw['formula'].apply(Composition)

featurizers = [

ElementProperty.from_preset("magpie"),

OxidationStates(), # May fail for some elements

AtomicOrbitals(),

BandCenter(),

]

df_featurized = df_raw.copy()

for fz in featurizers:

try:

# Add ignore_errors=True to skip problematic entries

df_featurized = fz.featurize_dataframe(df_featurized, col_id="composition", ignore_errors=True)

except Exception as e:

print(f"⚠️ Failed to apply {fz.__class__.__name__}: {e}")

# Keep only numeric columns

df_final = df_featurized.select_dtypes(include=[np.number])

# Drop rows where band_gap is missing

df_final = df_final.dropna(subset=['band_gap'])